Geology

Snæfellsjökull Glacier

Snæfellsjökull National Park is the westernmost part of Snæfellsnes and its area is 183 km2. To the south, its border lies around the eastern edge of Háahraun in the land of Dagverðarár and to the north on the eastern border of Gufuskálaland. The glacier cap of Snæfellsjökull is within the national park. The national park is unique among Icelandic national parks in being the only one with relics from the extermination of previous centuries.

The beach of Snæfellsness is diverse, alternating between rocky scales, beaches with light or black sand and steep sea cliffs with bustling birdlife during the breeding season. The lowland within the national park is mostly lava that has flowed from Snæfellsjökull or volcanoes in the lowlands. The lava is mostly covered with moss, but in between you can find beautiful, sheltered bowls with lush vegetation. The lowland on the southern side of Snæfellsnes is an ancient seabed that has risen since the end of the Ice Age. The hammer belts up from the lowlands are therefore old sea hammers.

The landscape

Snæfellsjökull towers majestically over the surroundings and you can clearly see how lava flows and lava waterfalls have flowed down its slopes. Its foothills, such as Hreggnasi, Geldingafell and Svartutindar, are varied in shape. Eysteinsdalur rises from the lowlands on the north side, but there you come to a different landscape, a valley surrounded by mountains that call for legs willing to walk. Higher up in the country and closer to Jökulhálsi, there are pumice flakes and land that has recently emerged from a glacier.

There are several beautiful waterfalls in the area. Klukkufoss is at the foot of Hreggnasa and is surrounded by rock. A little further east, in Blágil, two waterfalls fall into one gorge and they have been named Þverfossar.

Geology

The geology of Snæfellsness is extremely diverse and geological formations are from almost every period in Iceland’s geological history. The volcanic system associated with Snæfellsjökull is a strong landscape ensemble and shows traces of individual volcanic eruptions, both from the last glacial period and after the end of the ice age. The glacier last erupted around 1800 years ago, but the volcano is still believed to be active. The system is approx. 30 km long and extending from Mæifelli in the east to Öndverdarnes in the west and even further than more than 20 lavas belong to the system. The lifeblood of the volcano system is a magma line that lies at a depth of several kilometers under the glacier itself.

Lava formations

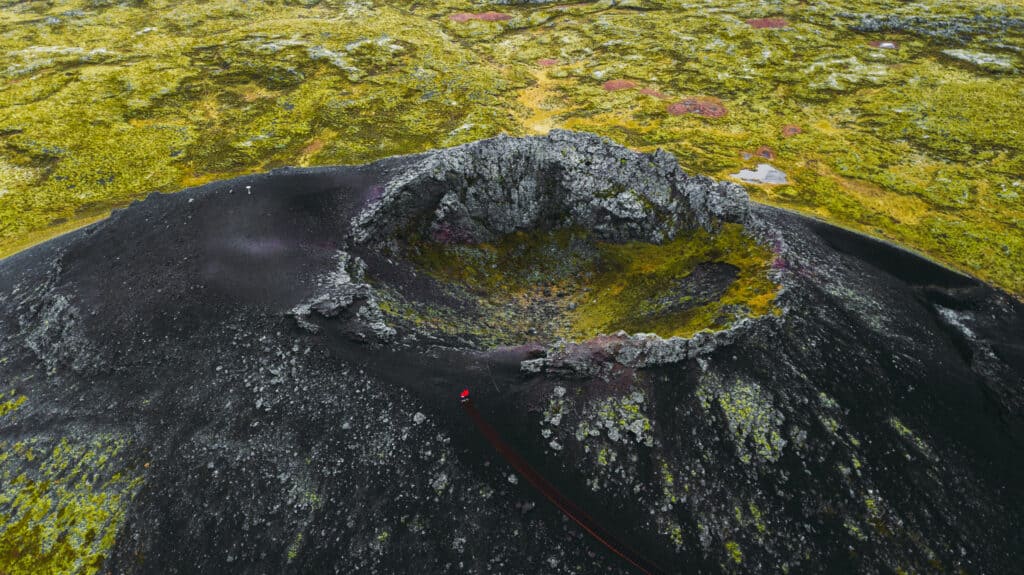

In and around the national park, most of the geological formations are from the last glacial period and modern times. The mountains north of Snæfellsjökull are made of tuff and have been formed by eruptions under a glacier or in the sea. Svaltúfa is most likely the eastern part of a crater that has erupted into the sea, and Lóndrang crater plugs. Lavas are prominent in the landscape of the national park, both rough apple lava and smoother slab lava. A large part of them has flowed from Snæfellsjökull, both from the top crater and from craters on the slopes of the mountain.

The lava formations are varied and beautiful, and the area is rich in caves. Tourists are strongly advised against going there unless accompanied by acquaintances. People may be at risk of collapse in some of the caves, and in others there may be sensitive lava formations. Guided tours are offered in Vatnhelli, one of the most beautiful caves in the area. There is a unique opportunity to learn about caves and how they are formed (link to the Vatnhellis page). In the lowlands are the volcanoes Purkhólar, Hólahólar, Saxhólar and Öndverðarneshólar, and all around are lava that has flowed from them.